Eugenics: the Upward Path

By Jan Keown

The impact of biological science on modern social thought is one of the most compelling dramas in all of human experience. On the one hand, for the first time we now understand some of the underlying mechanisms of the creation and transmission of the human characteristics. We know how heredity and environment interact to augment or degrade the quality of races and nations. Moreover, we now have the ability to manipulate both factors in order to produce a race of superior human beings who could be the embodiment of that most ethereal of our dreams: the Nietzschean Superman.

As fate would have it though, these advances in knowledge have come at a time when the world is in the grip of extremely destructive and irrational forces – a time when the ruling powers and the thoughtless masses alike worship the false god of universal human equality and see the devil in any dream of human betterment.

Overcoming these negative forces – or, at least, bypassing them – will be the mission of all progressive and racially conscious men and women for the foreseeable future.

In the beginning, natural forces of selection ensured that, on the average, each generation of our ancestors was stronger, tougher, and cleverer than its predecessors. The environmental pressures of the Ice Age world sloughed off the dead wood of our race with machinelike efficiency.

************************

“We drown the weakling and the monstrosity. It is not passion, but reason, to separate the useless from the fit.” - Seneca

************************

And we may with reasonable safety assume that the earliest Europeans possessed the healthy pragmatism regarding defective specimens of their own kind which is usual among primitive tribesmen of other races even today: useless mouths were a burden which the noble savage was uninclined to support. The Roman statesman Seneca stated the case for these primitive eugenicists when he wrote, in the first century of our own era, “We drown the weakling and the monstrosity. It is not passion, but reason, to separate the useless from the fit.”

The upward evolutionary spiral continued until the end of the Ice Ages, resulting in the Cro-Magnon man who was superior physically, and perhaps intellectually (judging from his larger brain), to anything we know today.

With the dawn of the Neolithic era and the coming of the agricultural economy, natural selective pressures eased, and sentiment began to interfere with a rigid pruning of inferior human material. Inevitably, while technology and social organization advanced, the quality of our ancestors imperceptibly began to decline.

Eventually, in place of the reflective eugenics of the tribal primitive, a new form of human quality control began to take shape in Classical Greece. The need of the city-state for healthy warriors coalesced with the Greek ideal of physical and intellectual perfection to produce, in Sparta, the first government-administered eugenics program of which we know.

Always outnumbered, ruling a resentful helotry and continually occupied with warfare or preparation for warfare, Sparta took great care to safeguard the quality and quantity of its citizens. There were penalties for celibacy and for late marriage, as well as for a bad marriage. A Spartan who fathered three children was excused from the night watch, and after his fourth child he was exempt from taxation.

All newborns were subject to an examination by the Elders. The child was taken to the Council Hall, and if it met the standards of the nation it was accepted. If found wanting it was hurled into an abyss on the slopes of Mt. Taygetus. “It was better for the child and the city that one not born from the beginning to comeliness and strength should not live,” was the sentiment attributed by Plutarch to Sparta’s great, semi-legendary lawgiver, Lycurgus.

Xenophon testified in the fourth century B.C. that the Spartan eugenics produced a race unparalleled in vigor: “It is easy to see that these measures produced a race excelling in size and strength. Not easily would one find people healthier or more physically capable than the Spartans.

With the decline of the Hellenic age, the ideals of the Greek eugenics disappeared from the world scene. Indeed, during her later days, forgetting Seneca’s precepts, Rome so neglected the quality of her people that the great edifice of her Empire staggered and then fell before the vigor of the unspoiled Germanic tribes of the misty North.

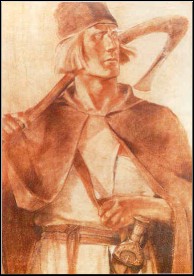

These hardy people, so magnificent in their pagan naturalness, carried all before them. The momentum of their onrushing energies took them to new heights of achievement which culminated in a world empire and the cultural-technical miracle which we know as Western civilization.

These accomplishments were accompanied, one regrets to say, by a new onset of the insidious process of racial degeneration – a process which had earlier been held in abeyance by the healthful and natural life-style of the uncivilized North. This is always the price paid for a preoccupation with the externals of life, and a neglect of its essence. But in the middle of the last century two men emerged who would offer a new opportunity to reverse the downward trend in racial quality: Charles Darwin and Francis Galton.

|

| FRANCIS GALTON |

Galton was born in 1822 into a talented, middle-class English family. Endowed with a soaring intellect, he was a marvelous example of the Victorian gentleman-scholar. He made significant contributions to geography, meteorology, anthropometry, and criminology.

The turning point in Galton’s intellectual life came with the publication in 1859 of The Origin of Species by his cousin Charles Darwin. Galton said of this event, “Its effect was to demolish a multitude of dogmatic barriers by a single stroke, and to arouse a spirit of rebellion against all ancient authorities whose positive and unauthenticated statements were contradicted by modern science.”

In particular, its effect on Galton was to initiate in him a lifelong concern with the science of racial improvement. He coined the term “eugenics” for this science, from the Greek words meaning “well born.” Galton devoted the remainder of this life to thinking, writing, and lecturing about the concept of the uplifting of the race through wise breeding.

Galton saw that the welfare of a nation was guaranteed not by any material resource it might possess, but by the collective hereditary qualities of its citizens. He was convinced that by suitably modifying the social environment it was possible to gradually raise the physical, mental, and moral level of successive generations. By the same token, he saw processes at work which, if nothing else was done to intervene, could permanently cripple the nation. He wrote in the 1894 National Review, “It has now become necessary to better the breed of the human race. The average citizen is too base for the everyday work of modern civilization.”

Galton also understood the nature of the principal obstacle in the path of the reforms he wanted to introduce. As he put it, “…there exists a sentiment, for the most part quite unreasonable, against the gradual extinction of an inferior race.”

When he dies in 1911 Francis Galton left a world which he had changed profoundly. He had forged a new way of looking at man and at life. The reverberations of his hammer blows are still echoing around us.

While he created an imposing theoretical framework, however, Galton never really attempted to put his idea into practice. In fact, the father of eugenics never fathered any children of his own. To see the eugenics idea in action we must look to the small-town New England of the 1830’s. Utopian communities were not uncommon in the 19th-century America, but the Oneida Community was unique, as was its leader, John Humphrey Noyes.

Noyes was born in 1811 in Brattleboro, Vermont. In 1833, during one of the religious revivals that were sweeping New England, he adopted a creed known as Perfectionism, which held that man can achieve a state of sinless perfection. He became so adamant in his beliefs, however, that he alienated his fellow Perfectionists and was declared

persona non grata by them.

|

| JOHN HUMPHREY NOYES |

Not one to be discouraged easily, in 1841 he decided to start his own group, in Putney, Vermont, beginning with himself, his wife, his brother, and his two sisters. Within a short time the group’s membership had increased to 35 persons.

Always the dominant personality and ideological fountainhead, Noyes evolved an idea which was to prove vital to the eugenics program which lay ahead for his group. His doctrine of “complex marriage” provided the basis for a genuine social revolution in miniature. The theological justification is obscure, but in effect it meant that everyone in the group was married to everyone else. In fact, exclusive love was declared sinful.

On practical grounds, marriage was seen as undesirable because it prohibited scientific selection and limited the best males to the number of children that one woman could produce. Noyes said, “Certainly, scientific propagation is impossible so long and so far as mating is done by promiscuous scrambling, which is the very nature of marriage. If the time has really come for scientific propagation, then the time has come for the departure of marriage and the reconstruction of society on the principles which allow science to lay its hands on the business of mating.”

Their unorthodox social arrangements eventually aroused the ire of their more conventional neighbors, and the group moved to Oneida Creek, New York, which was then a frontier settlement. Arriving in 1848, they began building their community. At this time they were 87 in number. Beginning from scratch they spent 20 years creating their utopia.

During this time Noyes prepared for the day when his projected eugenic breeding program, which he called “stirpculture” (from the Latin stirps, meaning stock or lineages), would begin. Evening lectures were given by breeders on inbreeding, judicious crosses, and other tricks of the trade.

By 1869 the stage was set for the first attempt at scientific breeding. In 20 years of hard work Noyes and his followers (by then numbering around 250) had built a thriving community. They had houses, farms, factories, printing presses, and money in the bank. They were united behind a dynamic leader and were of one mind and one accord as to how they should proceed.

The women who were to take part in the program pledged: “We have no rights or personal feelings in regard to child-bearing which shall in the least degree oppose or embarrass Mr. Noyes in his choice of scientific combinations.” The men likewise promised: “We desire you may feel that we most heartily sympathize with your purpose in regard to scientific propagation, and offer ourselves to be used in forming and combinations that may seem to you desirable. We desire to be servants of the truth. We are your true soldiers.”

A commission headed by Noyes had the final say over who would mate with whom. Usually a couple applied for permission to mate, but at times the commission took the initiative in selecting matches.

In the ten years between 1869 and 1879, 58 children were born as a result of the stirpicultural experiment. Of these, nine were fathered by Noyes himself, who was then in his sixties.

The results of the experiment were encouraging. No mothers were lost, and no deaf, dumb, blind, crippled or idiotic children were born. Although no intelligence tests were given to the children, their longevity statistics are interesting. By 1931 the oldest of the “stirpicults” was 52, the youngest 41. According to actuarial statistics there should have been 45 deaths by that time, this rather high number reflecting the high infant and child mortality rate in the U.S. population in the second half of the 19th century. In fact, however, only six of the 58 had died.

Noyes left the Oneida Community in 1876 in the wake of a religious dispute. It is ironic that while the founder of modern eugenics, Francis Galton, had rejected the Bible-based “creation” fable and the other Judeo-Christian myths, the only eugenic breeding community in America found is justification in the Bible and was wracked by Scriptural quibbles. Soon after Noyes departed, complex marriage and stirpculture were abandoned. In 1881 the community was dissolved.

Noyes, in retirement in Canada, claimed not to be discouraged by the collapse of the Oneida Community. He said, “We made a raid into an unknown country, charted it, and returned without the loss of a man, woman, or child.”

At about the time the Oneida Community was coming to an end, America was beginning to embrace the eugenics idea with a rising tide of enthusiasm. By the turn of the century the nation was entering an era which could almost be called the golden age of eugenics. The progressive movement welcomed biological reform as a natural corollary to political reform. The 26th President of the United States, Teddy Roosevelt, said, “Some day, the inescapable duty of the good citizen of the right type, is to leave his or her blood behind him in the world.”

Leading geneticists and other scientific and civic celebrities were solidly behind the movement. In 1906 the American Breeders Association set up a commission on eugenics, among whose members were botanist Luther Burbank, geneticist Edward G. Conklin, and David Starr Jordon, president of Stanford University and vice-president of the Boy Scouts of America. According to Jordan, “The blood of a nation determines its history.”

************************

[B]y 1928 three-fourths of the nation’s universities taught eugenics.

************************

Eugenics organizations were formed all across the country. Madison Grant, the noted author and president of the New York Zoological Society, formed the Galton Society in New York. Another group, the Eugenics Education Society, had branches in a score of cities. In 1913 the Eugenics Association was founded. The Eugenics Committee of the United States, later called the American Eugenics Society, began operating in 1822.

The new science of eugenics was highly regarded in the academic world of 60 years ago. In fact, by 1928 three-fourths of the nation’s universities taught eugenics.

Sterilization was proposed as a eugenic solution to the problem of crime. Vasectomy, which originally was a substitute for castration, was first performed in Indiana in 1899. The Indiana legislature passed the first state sterilization law in 1907, making sterilization mandatory for confirmed criminals, idiots, imbeciles, and other institutionalized people when deemed appropriate by an expert board. Thirty states had sterilization laws by 1931.

In 1924 eugenics advocates played a key role in gaining passage of the Immigration Restriction Act, which was intended to preserve the predominantly Nordic racial character of the United States. James J. Davis, President Coolidge’s secretary of labor, speaking in support of that act, said: “We should ban from our shores all races and all individuals who are physically, mentally, morally, and spiritually undesirable and who constitute a menace to our civilization.”

Five years after its greatest triumph, the eugenics movement met with disaster. With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 the eugenics societies dried up and blew away. The grim, immediate problems of economic survival took precedence over idealistic concerns for future well-being. Finally, the coming to power of the liberal-minority coalition under Franklin Roosevelt in 1933 drove the last nails into the coffin of the eugenics movement.

Ultimately, even had it not been for the disasters of Depression and FDR, that movement would have run up against its own limitations. All the talk, all the committees, all the college courses, despite their beneficial effects on legislation in the first quarter of the century, could not have achieved their desired ends. The movement was at odds with the democratic-capitalist spirit of the country. A meaningful eugenics program must be a prime national goal with the full support of a determined leadership behind it. It must be part of a total revolution involving a whole people.

Just such a revolution was coming to fruition in Germany in the fateful year of 1933, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler. Never before had a national government come to power fully committed to the biological ennoblement of the nation. In the words of Wilhelm Frick, Hitler’s minister of the interior: “The fate of race-hygiene, of the Third Reich, and of the German people will in the future be indissolubly bound together.”

Brave words were matched by action in the new Germany. Private organizations engaged in eugenics education, such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Genetics, and Eugenics, were reorganized as government agencies. On July 14, 1933, the Hereditary Health Courts were set up to supervise the sterilization of congenitally defective Germans. In their first year of operation over 50,000 sterilizations were performed.

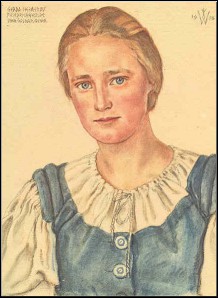

Pro-family and pro-child propaganda encouraged Germans to have large families. Marriage loans at no interest were made available to young couples, one-fourth of the principal being canceled with the birth of each child.

On December 12, 1935 Heinrich Himmler, the national leader of the SS, instituted the Lebensborn (“spring of life”) program. The Lebensborn concerned itself with families of especially good stock. It provided support for large families and help for expectant mothers and children. It fought against the abortion of healthy children and tried to raise the position of the unmarried mother.

|

| HEINRICH HIMMLER |

Germany was well on the way to a revolutionary new age of racial dynamism, but an aroused world Jewry had other ideas. The rest is history.

With the destruction of Germany the eugenics idea was “discredited.” Anyone since that time daring to express concern about problems of racial quality has found himself under attack by the New Inquisition. A taboo on racial thought in the academic world is rigidly enforced, and the new orthodoxy of human equality reigns without challenge.

Thinking about our genetic position today is an essentially unpleasant duty. The trends are all negative. Live in the modern industrial states of the West is as racially unhealthy as can be imagined.

It is ironic that in the midst of this racial disaster area the science of genetics is making tremendous progress. While the society around them lurches toward a biological debacle, the geneticists are gaining new knowledge at an exponential rate. What is lacking is the motivation on the part of the governmental-academic establishment to use this new knowledge for the improvement of the race.

Nevertheless, the knowledge is available to those who are willing to use it. Although some if its applications require all the machinery of modern high technology, others are relatively simple, needing little more than a willing and informed group of men and women.

One of the simplest and potentially most effective applications of the new knowledge is artificial insemination. In the 1940’s Dr. A.S. Parkes found that sperm treated with glycerol could be frozen and stored for an indefinite period. Concurrently, the Nobel Award-winning geneticist, H.J. Muller, proposed a national sperm bank, which every woman could draw on to have children by exceptional fathers. This idea has been revived recently – and hysterically condemned by the controlled media.

On the distaff side, new techniques can also be used to increase the spread of desirable genes. Hormone injections can cause a female to superior quality to super-ovulate, releasing up to 30 eggs at one time. After surgical extraction and fertilization the eggs are implanted in average, healthy females, where they are carried to term.

Controlled inbreeding could also have a pronounced eugenic effect. As opposed to outbreeding, which tends to hide and spread recessive defects, inbreeding can be made to have a cleansing effect on the gene pool. By sterilizing any defective offspring, it is possible eventually to produce faultless, true-breeding thoroughbreds.

Experimenters with fruit flies have inbred brothers and sisters for 75 generations without loss of fertility or vigor. The same has been done with rats for 25 generations.

There is also an interesting human precedent. In ancient Egypt brother-sister marriages were much in vogue, especially among royalty. James G. Frazier writes in The Golden Bough, “Marriage between brother and sister was the best of marriages, and it acquired an ineffable degree of sanctity when the brother and sister who contracted it were themselves born of a brother and sister, who had in their turn also sprung from a marriage of the same sort.”

During the long XVIIIth Dynasty (1570-1320 B.C.), generally regarded as one of the greatest periods of ancient Egypt, this practice was carried on for centuries. All indications are that the results were excellent. The mummified bodies which the Egyptians thoughtfully provided for our examination are uniformly clean-featured and well-formed.

It must be realized that effective eugenic practices would involve a substantial amount of social and psychological reorientation in the group employing them. A really aggressive eugenics program would require extensive modification of the ordinary societal myths, norms, and biases. The benefits to posterity, however, would be incalculable: the biological equivalent of the old alchemist’s dream of transmuting lead into gold.

It seems obvious that the chances of eugenics principles being applied on a national scale anywhere in the West during the present era are nil. This society is rotting from within, undermined by contradictions which prevent it from facing reality and confronting the most basic of problems. With the old order paralyzed by its own outdated values, it will be up to the standard bearers of a new order to guide our people through the coming crisis and ultimately lead them to the greatness which is their destiny.

The upward struggle of life is far from ended. Our present stage of evolution is but a way station on the path to unimaginable future glories. Friedrich Nietzsche put it this way in his Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The Superman is the meaning of the earth. Let your will say, ‘The Superman shall be the meaning of the earth.’”